Each spring biologists from the NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) head out to the beaches along Lake Michigan to check in on juvenile lake whitefish. This popular, mild-tasting native species is the most popular commercial fish in the Great Lakes. Our scientists use special nets to count juvenile whitefish and keep tabs on how these fish are faring as the Great Lakes change. Numbers show that the species has declined dramatically, and GLERL is working to determine what is causing this.

What is a Lake Whitefish?

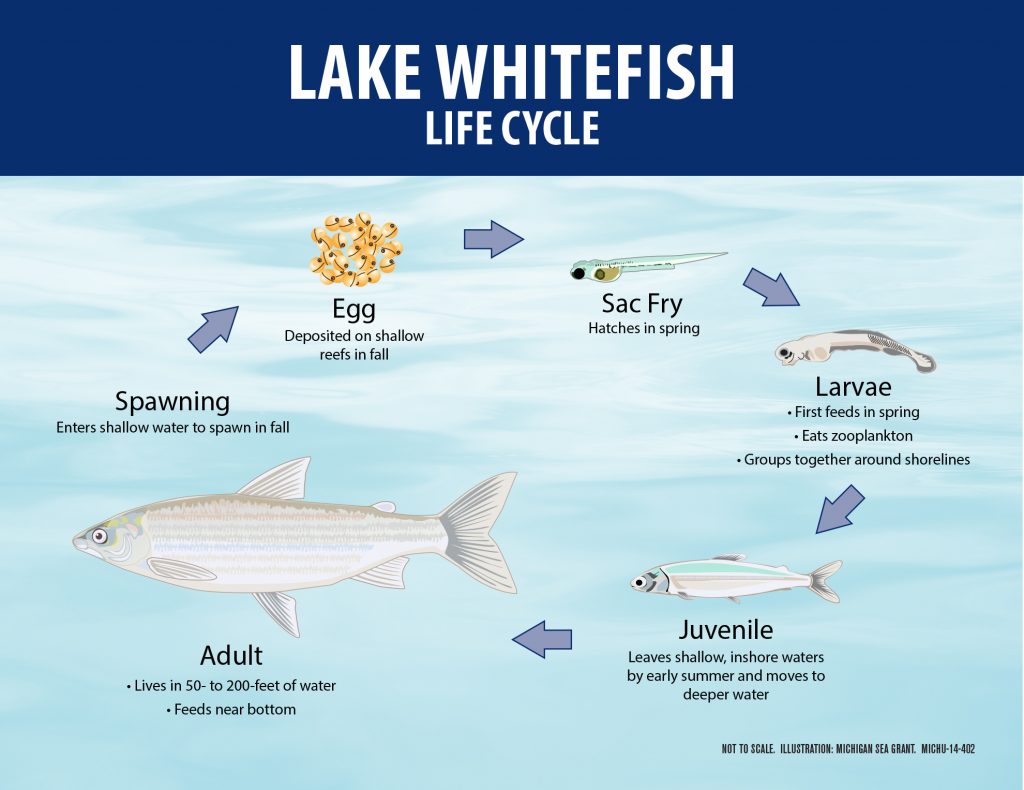

Lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) are a native species to the Great Lakes that are a popular and valuable commercial fish. Related to salmon and trout, they are prized for their exceptional flavor and are economically valuable to the Great Lakes. They live and feed in the benthic zone of the lakes – in the dark, cool depths near the lake bottom. Lake whitefish prefer cool water and spend much of their time offshore except during the spawning run in late fall where they migrate to shallow reefs, rocky channels, and rivers to lay their eggs. Eggs then overwinter in those locations and hatch in the early spring, when the larval fish begin looking for food. Their diet historically consisted of an energy-rich, shrimp-like amphipod called diporeia. However, diporeia have been in drastic decline in the Great Lakes over the past several decades, so lake whitefish must find poorer quality food such as mussels, other invertebrates, and small fish to eat.

Why are Lake Whitefish Popular?

Lake whitefish have long been an important commercial fishery in the Great Lakes. According to the Michigan Sea Grant, in 2020 they made up 89 percent of the catch in Michigan commercial fisheries and 95 percent of the sales. Well known for their mild flavor they are likely to end up on restaurant menus throughout the Great Lakes region and beyond. They also support a popular recreational fishery for ice anglers on Green Bay, where over 110,00 fish are caught annually, as well as smaller recreational fisheries around piers throughout the Great Lakes.

What is Affecting the Status of Whitefish Populations?

Lake whitefish are showing a decline throughout much of the Great Lakes, especially in the main basin of Lake Michigan. According to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, commercial harvest in the early 1990s was around 8 million pounds a year, but by 2020, harvests had declined to just above 2 million pounds a year. Recruitment describes the critical process through which fish populations regenerate themselves by laying eggs, producing larval fish that can thrive when conditions and food supplies are optimal before transitioning to mature fish that become desirable for catch. Researchers from GLERL along with partners from other agencies and tribes are working to identify what factors are affecting whitefish recruitment, and identify any recruitment bottlenecks that are contributing to the decline of whitefish populations.

How are We Investigating Whitefish Recruitment?

After hatching in late winter, larval lake whitefish spend their time in the nearshore areas of the lakes. They need a steady supply of food in order to thrive and grow, typically eating zooplankton in the water. Researchers are able to capture larval fish for studies in this habitat by manually pulling a seine net along the beach. The seine is a 150 foot long mesh net that is pulled out from the beach and then manually worked back towards the shore. Any fish captured in the seine are concentrated to the back of the net for easier sorting.

Spottail shiners, banded killifish, round gobies, and emerald shiners are all common bycatch species; those are counted and returned to the water. Any whitefish captured are counted, measured, and their diet is analyzed by examining their stomach contents under a microscope. Additionally, lake and weather conditions are recorded, such as water temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, substrate, wave height, wind speed and direction. A zooplankton sample is also taken to allow researchers to compare what’s in the water to what the whitefish have eaten to estimate how much food is available to them.

Biologists at GLERL’s Lake Michigan Field Station in Muskegon, MI have been using seine nets to sample larval whitefish on the beaches near Muskegon, Grand Haven, and Montague every spring since 2014. This long term dataset is important for understanding the health of the fishery as it takes whitefish five to seven years to recruit to full adulthood. Once larval whitefish have been captured at each site and examined in the laboratory, GLERL biologists can study ecological changes that are happening over time to understand how likely young fish will be recruited to adult stages and become part of the commercial fishery.

How are Larval Whitefish Doing?

During most years, larval fish numbers have been low in GLERL sampling in southeast Lake Michigan, indicating there will be fewer fish to grow to adult life phases than historical numbers show. Furthermore, even during the years when catch numbers were highest, there was little evidence in subsequent surveys of mature whitefish by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources that these fish survived to adulthood, reflecting poor recruitment. One reason may be that these fish do not have enough food to quickly grow beyond the larval stage (where they are vulnerable to predators or starvation). GLERL’s diet analyses indicate that larval lake whitefish require certain types and sizes of food at different phases of life. In order to thrive, larval whitefish and the right types of food (i.e., different species of zooplankton or larger prey) have to be in synchrony in order for the whitefish to successfully survive and grow into their next stage of life. Many factors can affect this harmony, including competitors such as invasive mussels, predators, and how winter and spring weather conditions are suitable for both plankton and fish larvae. GLERL’s research is used by fishery managers to determine how to manage sustainable and profitable fisheries in Lake Michigan and the other Great Lakes. Beach seining surveys of larval whitefish have become a critical clue on why fishery catches have dropped in the Great Lakes. This study is very important to fishery managers who are working to ensure Great Lakes fisheries are sustainable and profitable, and people are able to enjoy whitefish on their table for many years to come.